“New York is a city of unnoticed things,” begins the essay that opens “A Town Without Time,” a new collection of New York writings by Gay Talese. Talese then deceptively goes on to list the things he does has noted: chestnut sellers, pigeons, doormen, copy boys, ants.

For more than sixty years, Talese has made it his job not to miss much. Whether his subject is an icon (“Frank Sinatra Has a Cold”), a monument (his cinematic account of the construction of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge), the tragic or the feline, he always works with the same novelistic verve and with the same enthusiasm observed. eye. And of course he took note of what everyone was wearing.

“When I describe people, I describe what they look like,” Talese says. “Clothes are important, especially when you get old.”

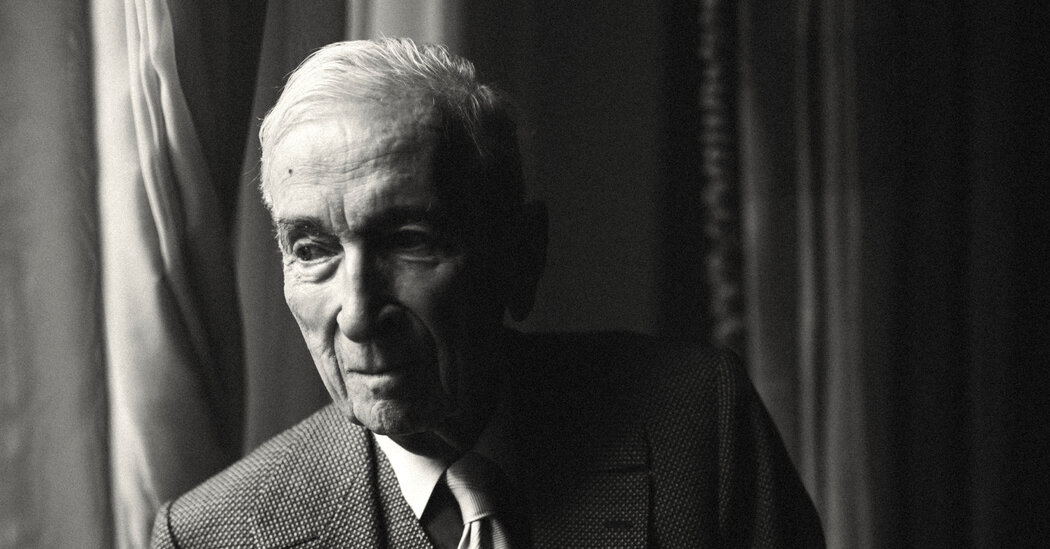

If you walk through a crowded room with 92-year-old Talese, you will be approached by men who want to talk about suits. At a recent Christmas party packed with writers, politicians and tastemakers, Talese, dressed in a three-piece gray wool suit with a yellow silk tie with blue stripes, was stopped every few steps by bold names (and at least one journalist) eager to talk about the issue . the finer points of menswear. A young novelist asked how much a custom pattern would have cost in 1980.

“Three thousand,” Talese said, although most of the handmade “50s or 60s” suits in his collection date from the 1950s.

Over the years, the suits have served as a kind of armor: “I hid behind the clothes,” Talese said. They have also been an advertisement. From the age of 11, when his father – ‘the James Salter of tailors’ – dressed him as ‘a kind of little billboard’, wearing a suit gave me a sense of separation.

This sense of hiding in plain sight – of creating a kind of flamboyant anonymity – permeates ‘A Town Without Time’. It’s tempting to see Talese as an avatar of a vanished, sepia-toned city. In fact, he has always been a proud anachronism, a fedora-wearing copy boy and, even into the Gonzo years of the 1960s and 1970s, someone who, he said, never owned jeans.

He stands by his decision. Today, he and his wife, retired publisher Nan Talese, live next to a 16-story medical building. He sees cars stopping and people getting out to go to a doctor, and they are “terribly dressed, in blue jeans, sneakers, windbreaker,” he said. If only they would dress better, they would feel better, he is convinced. “When you look in the mirror, you feel better,” he said. “You shouldn’t have to spend so much time in doctors’ offices.”

Although he now walks with the aid of an elegant Italian cane and has traded six nights a week in the city’s hot spots for life in the Midtown Brownstone where he has lived since 1957, Talese finds his New York as vibrant as ever .

As the title of your book suggests, you don’t mourn old New York. Is there anything you miss?

Elaine’s. I miss that place. Because today the city do sleep. PJ Clarke’s is open late, but I don’t always want a burger. People of course; I miss George Plimpton.

But actually this neighborhood hasn’t changed that much. I know people in this neighborhood, the drugstore, the tailor. I know the hardware store. Because I don’t have a supermarket or doorman, a number of supermarkets in the adjacent buildings help me. It really is a small town, at least in this area.

It is interesting to speak in terms of additions, rather than losses. Would you say you are an optimist?

At 92, to publish a book, and one that requires so much legwork… I am a very grateful person that my body and mind have persevered.

Nothing has changed. I show up, talk to people, see their faces. What an uplifting life.

Do you have a favorite from your New York stories?

I’ve never won any awards like the Pulitzer or anything like that. But one thing I’m proud of is my piece on the Verrazzano. When I’m long dead, someone in 35 years will want to know about that bridge. I was a chronicler of the nobody who put in the wrenches and screws. For me that was a big achievement.

We used to drive over the bridge, with the roof down, and that was ‘Daddy’s Bridge’. My daughters Catherine and Pamela thought I owned that bridge. I didn’t tell them that wasn’t the case for a long time.

You’re a journalist by training—a piece about your early days at The New York Times is included here—but you say your main inspiration as a writer comes from fiction.

What I wanted to do was take the short story form I had in mind from the time I was in high school: Robert Penn Warren, Ernest Hemingway, DH Lawrence, William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, Joseph Conrad, Seymour Krim. Mary McCarthy was one of my favorites. I wanted to be a nonfiction short story writer. I have not changed the way I work or research in the 67 years I have been publishing. I am a record holder.

And you have a famously complete archive.

Yes. I record everything. And of course my letters – but letters are unbelievable. What I wrote in those letters is not always true.

I wrote terribly about my marriage. I can’t take it back. I’m going to keep it there. But it’s not true.

I’m almost 93. My wife is 92. I don’t want to leave her now, but ten years ago there were times when I didn’t want to be with her. How can you be honest? What is honesty?

One motif in your New York writing is baseball.

When I was a kid in Ocean City, NJ, in 1944, the New York Yankees came to Atlantic City for spring training because you couldn’t use the gas to travel further during the war.

And then along came sportswriters. You know, there were seven newspapers at that time. The New York Times had a deaf man named John Drebinger, he had big ears, couldn’t hear anything, but he knew Babe Ruth. I was so enamored with great writers who traveled with a team. God, what a job, what a job.

New York came to Atlantic City. I saw New York in the role of the team and became a sports journalist. It was my first job.

And your first job in New York was as a copy boy?

Yes. And when I was a copy boy at the New York Times in 1953, men still wore suits and jackets and ties and sometimes fedoras. Especially many World War II correspondents in the last years of their careers. Those guys who had been bureau chiefs in Paris, Rome or London were very, very well dressed, with foreign tailors.

Well, that has changed!

Men don’t dress in New York anymore. You go to a good restaurant and the women look great. The men dress terribly.

Would you ever move?

I can’t remember an unhappy day in New York City. I can’t imagine leaving.